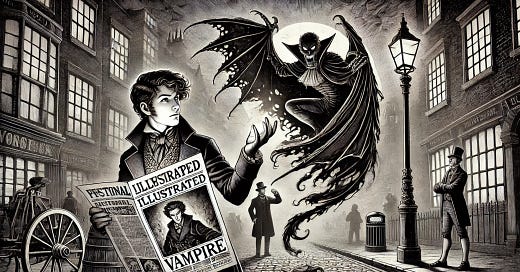

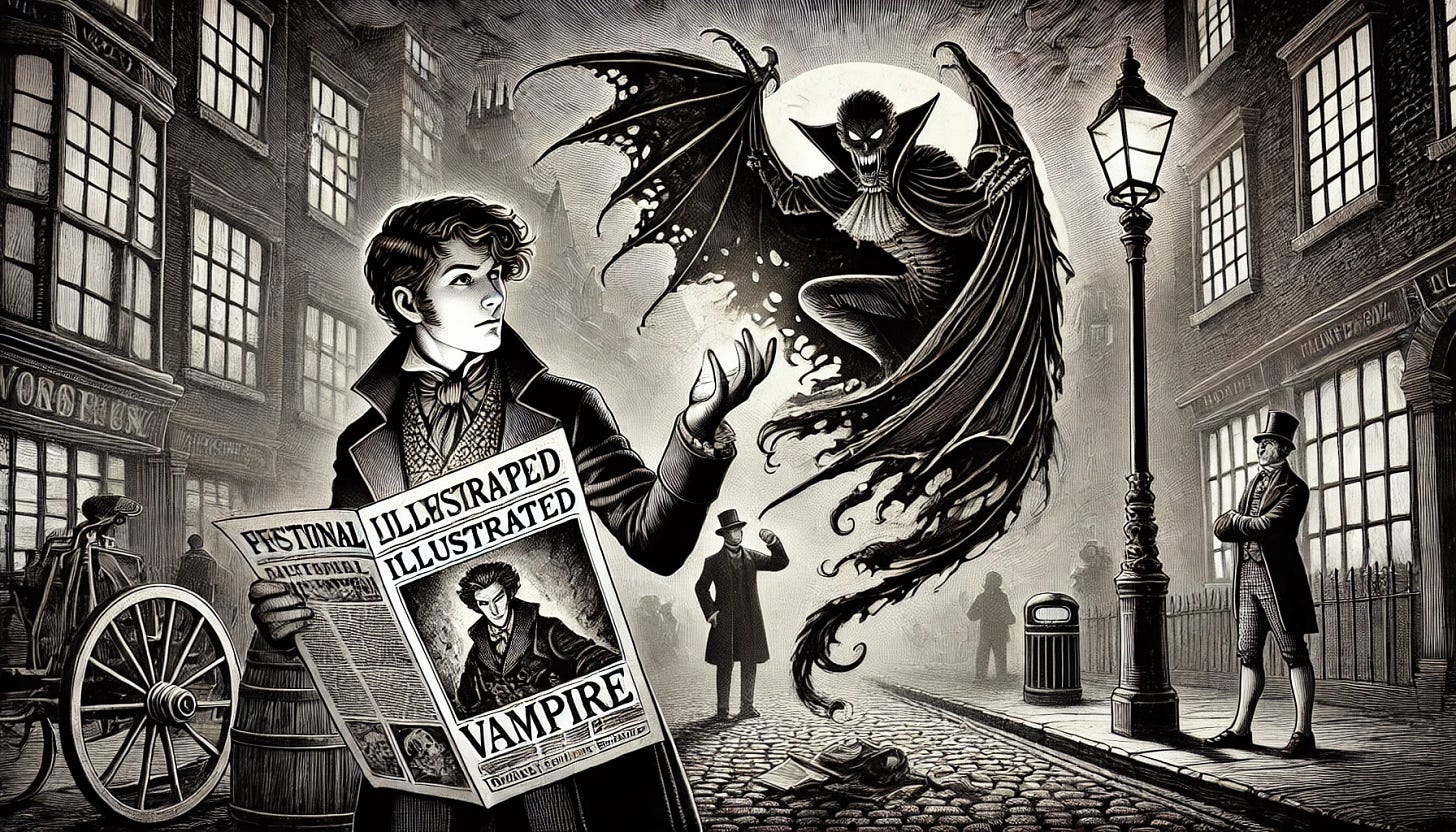

"Fresh blood! Fresh blood!" The cry echoes down a foggy London street in the mid-1840s, but it's not a murderer advertising their crimes – it's a teenage boy waving a paper illustrated with a stark woodcut of a vampire's victim. These "patterers" would draw crowds with theatrical performances of the latest penny dreadful chapters, turning street corners into impromptu stages. For one penny – less than the price of a loaf of bread – passersby could own the latest installment, its dramatic cover illustration promising horrors within.

Urban Anxieties and Paper Empires

In rapidly industrializing Victorian cities, where crime seemed ever-present and traditional social bonds were fraying, these cheap weekly publications helped readers process their anxieties about urban life. The stories were printed on paper so cheap it sometimes contained visible pieces of straw, yet they sold in astronomical numbers. Each issue would pass through multiple hands, shared among families, friends, and coworkers, multiplying their actual readership far beyond their sales figures.

The Mastermind of Mass Market

The mastermind behind much of this bloody business was Edward Lloyd, a publisher who understood something fundamental about media economics: scale changes everything. While traditional "three-decker" novels cost roughly a month's wages for the average worker, Lloyd's penny publications democratized reading while building a sustainable business model. The term "penny dreadful" itself began as critics' sneering dismissal but became a badge of pride for both publishers and readers.

Blood and Ink: The Stories That Sold

The content itself was a brew of horror, crime, and social commentary. James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest's "Varney the Vampire" ran for 232 weekly installments, filling nearly 900 pages when collected. The same duo created Sweeney Todd, whose story of cannibalistic meat pies played on very real Victorian fears about food adulteration in London's unregulated markets. Each issue featured dramatic woodcut illustrations that brought the macabre stories to life – scenes of vampires stalking victims, demons emerging from shadows, and mysterious figures in London's fog-shrouded streets.

G.W.M. Reynolds' "The Mysteries of London" mixed true crime with social commentary, becoming one of the era's longest-running and most successful serials. Pierce Egan the Younger turned historical outlaws into heroes with "Robin Hood," while his "Dick Turpin" series ran for hundreds of episodes, romanticizing highwaymen for generations to come. Even the young adult market was born here – school stories like "Tom Wildrake's Schooldays" created templates that would influence literature for the next century.

The Writers' Room

Lloyd cultivated different authors for different audiences, testing new series with small runs and quickly scaling up successful titles. Writers worked at breakneck speed, sometimes collaboratively, to meet the insatiable demand for new stories. Charlotte Mary Stanley, one of the few known female writers in the space, brought romantic elements to crime stories, broadening their appeal beyond the traditional male audience.

Distribution Revolution

The infrastructure that supported this literary revolution was just as fascinating as the stories themselves. As Britain's railway network expanded, W.H. Smith's railway bookstalls became Victorian England's first content distribution network (as highlighted in a previous post here). The rapid growth of rail travel created a captive audience of passengers with time to kill and a penny to spend, transforming how publishers reached their readers.

Hooks, Cliffs, and Staying Power

The storytelling techniques were revolutionary for their time. Penny dreadfuls mastered the cliffhanger, often ending chapters mid-scene to ensure next week's sales. They mixed fact and fiction freely, reminiscent of today's "Law & Order" and its stories "ripped from the headlines." When Prest wrote about Sweeney Todd's meat pies, he was tapping into contemporary newspaper headlines about food scandal investigations. The stories became so embedded in popular culture that many readers began to believe they were based on true events. Some still do – tour guides in London continue to point out the "historical" location of Sweeney Todd's barbershop, despite the character being purely fictional.

The Penny Profits

Lloyd and his contemporaries understood that media profitability could be achieved not only through premium pricing, but through combining accessible price points with massive scale. His penny dreadfuls generated lower margins than traditional books but reached audiences hundreds of times larger. Modern content creators might be surprised to learn how much of their playbook was written in cheap Victorian ink, accompanied by woodcuts of vampires and demons.

Stay tuned.